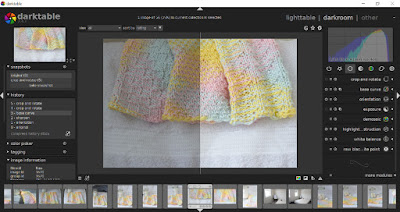

The levels tool can be found in most image editing programmes (including my favourites, darktable and GIMP) but for the purposes of demonstration, I'll stick to using darktable only. I will also be using a simple image containing various tones to demonstrate the effects of levels adjustments. I encourage you to download this image and play with it on your own; the easiest way to learn is through hands-on practice:

|

| Right click and save as to download to your own computer. |

The basic anatomy of the levels tool is a box containing the histogram for your image, with a black-to-white gradient at the bottom and a set of three sliders. The levels tool in your software of choice may look slightly different, but it should function similarly. In darktable (and in many other editors), you will also see three eyedroppers; these allow you to move the position of the sliders more precisely (more on that soon).

If you're familiar with your luminosity histogram, the levels tool will probably be reasonably intuitive. The gradient at the bottom represents the distribution of tones in your image--it's sort of a guide to reading your histogram. On the left, you have your darkest tones, in the middle you have your midtones, and on the right, you have your lightest tones.

The sliders are used to tell your image processor which tones in the original image should be rendered as pure black, which tones should be rendered as pure white, and where your middle grey should be positioned. Their default positions, therefore, will be at the far left, the far right, and the middle of the histogram respectively.

If you slide your black point slider to the right, the amount of black in the image will increase--anything that was darker in the original image than the new position of your slider will be rendered as pure black. Note that the middle slider will automatically be repositioned in the exact centre between the new black point and the white point. Note also that the histogram for your image (at the top right of the screen) will also change to reflect the new tonal distribution:

|

| Changing the black point (and with it, the mid-point). |

Likewise, if you move your white point slider to the left, all of the tones in the original image that are lighter than its new location will be rendered as pure white. Again, the midpoint slider will automatically reposition itself to the centre between the black and white points:

| |

| Moving the white point. |

Moving the middle grey slider is a little trickier to explain, but basically, the slider determines which original tone will now be rendered as middle grey. Therefore, if you move the slider to the left, your overall image will lighten (although your black point and white point will not be altered unless you choose to move them), because you are telling your editor that a tone originally closer to black should be lightened to midgrey, and therefore the other tones will also lighten to reflect the new distribution of tones. If you move the midpoint slider to the right, the overall image will darken, as you are telling your editor that it should darken what was originally a lighter tone into middle grey. This is easiest to understand by playing around with the sliders yourself.

| |

| Lightening the image by shifting the midpoint. |

If you want to precisely place the black point, white point, or midpoint, you can use the eyedroppers. Simply click on the eyedropper associated with the point you wish to change, then click on the area of the image that you wish to place at that point.

So how does this work in colour? Let's play around with two examples. First, a colour distribution:

| ||

| I encourage you to also download this image for practice. |

Let's try moving the black point...

|

| Shifting the black point. |

...and now the white point...

|

| Shifting the white point. |

...and now the midpoint...

|

| Shifting the midpoint. |

...and now all three points:

|

| Shifting black point, midpoint, and white point. |

See how the levels tool can dramatically alter the look of your image?

Finally, let's play with a real-world example:

|

| A Nova Scotian sunset. |

See what happens if we shift the black point?

|

| Moving the black point. |

What about if we shift the white point?

|

| Moving the white point. |

And finally, what if we move the midpoint?

|

| Moving the midpoint. |

The levels tool is just that simple. And, to make life even better (at least in darktable), adjusting your levels will adjust your image in real time, letting you tweak it exactly to your liking. It's an easy tool that makes a powerful difference.