As smartphone cameras become increasingly sophisticated, many people are abandoning traditional compact/point-and-shoot cameras and instead relying solely upon their phones for their photographic needs. Is this a viable strategy for the fibre artist? Let's consider some of the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Budget

If you already have a cellphone with a decent camera, sticking with it as your fibre art camera certainly makes financial sense. At worst, you might need to buy some more memory, or a cable to transfer your photos to your computer--and chances are, you won't even have to do that.

A compact camera, on the other hand, will cost you some more money if you don't already have one. New point-and-shoots that are worth buying are, on the lowest end, somewhere in the range of $100. Used, you can get a camera much more economically, but it won't come with the same guarantees as a new one. If you're on a tight budget but decide that you want a compact camera, consider buying a used, older model through a reputable store such as Henry's (in Canada) or Adorama or B&H (in the States). Another option would be to look for a free or very inexpensive camera on a local buy/sell/trade site.

Convenience

Chances are, your phone camera is going to win when it comes to the convenience factor. Most people I know have their phones within reach the vast majority of the time. A dedicated compact camera, on the other hand, is not something most people drag around with them. Additionally, you're less likely to notice a missing memory card or a dead battery in a compact camera that you don't use regularly.

That said, you can get point-and-shoot cameras that fit easily into your pocket, so if you're leaning towards a compact camera, don't worry too much about portability.

Mindset

This may not affect everyone, but it's worth considering whether having a dedicated compact camera will get you in a more photographic mindset. Is it easier for you to take better photos when you're using a more traditional camera? For me, when I'm snapping a cellphone picture, I tend to forget everything I've ever learned about photography (don't ask me why). Having a standard camera in my hands (whether a DSLR or a point-and-shoot) just does something to me psychologically that results in better images.

Sensor

This one goes to the compact camera. Almost all compact cameras will have a larger sensor than their phone camera counterparts. A larger sensor typically translates into better image quality, especially in low-light conditions. If you're shooting in well-lit conditions, a larger sensor is still advantageous, but won't make as much of a difference.

Zoom

Almost all compact cameras will have at least some optical zoom. Almost no smartphone cameras will have any optical zoom. If zooming is important to you, then a compact camera is the way to go. Never use digital zoom if you care about your image quality!

Zooming does more than simply enlarge things that are far away. Zooming in has the visual effect of compressing the elements in the photo--of making them appear closer together. A wide angle, on the other hand, will make elements that are closer to the camera look significantly larger than elements further away. (Ever wonder why your nose looks so big in selfies? It's probably because you shot the selfies with a wide angle lens). A zoomed-in portrait is generally going to be more flattering to the subject than one taken with a wider angle. More zoom can also give you a shallower depth of field (in other words, it can help to blur your background), depending upon the aperture used, the distance of the camera to the subject and the subject to the background. Optical zoom is probably the biggest benefit of a compact camera over a smartphone camera.

Ergonomics

This is going to come down to individual preference, but in general, a compact camera is going to be designed to be used as a camera, and will be laid out accordingly. A smartphone is going to be designed to be used as, well, as smartphone, and the camera ergonomics will be less of a priority. I personally find a dedicated camera to be much more ergonomically friendly than a smartphone camera, but your mileage may vary. One benefit of a smartphone camera over a low-end point-and-shoot, however, is touch screen focus: to focus on a specific element of your scene, you can simply touch it. The cheaper compact cameras tend not to have touch screens.

In the end, only you know your needs. At least now, though, you have a few things to consider when making your choice.

Showing posts with label photography - general. Show all posts

Showing posts with label photography - general. Show all posts

How I Shot It: Unassuming Socks

I'm thrilled to announce that my new pattern, Unassuming Socks, is now available for free in the May 2018 edition of Knotions Magazine! Although not my best photos ever (they were taken many months ago, and I'm still learning!), I thought it might be fun--and possibly educational--to write a post explaining how I shot the main pattern photos.

The Location

The photos were taken in my rather messy basement, on a February evening. Not much natural light happening there!

The Equipment

To get these shots, I used the following gear:

The Setup

This is an impressively professional and well-thought-out studio setup. Not.

I tucked an edge of the tablecloth into the top drawer of an old dresser that was sitting in the basement. Voila! A plain red backdrop is born.

I located the tripod several feet away from the backdrop, on its lowest setting. I placed the flash on the tripod, with the flash head pointed up and towards the white wall to the side of my backdrop (assuming I recall correctly, and that I am reading the light in my photos correctly).

The flash was connected to my camera via the Speedlite cord, which allowed it to be triggered off-camera. I situated the camera itself far enough away from my backdrop that I could shoot wide and crop later; this gave me a little more leeway in terms of where I could position myself and still be in the shot. The most professional part of all? I set the camera on a Wii Fit board with a rolled-up sock under the lens to prop it up just a little bit. Pro tips, y'all. Keep it classy.

The Process

The first step was to get the exposure right. Because my (cheap) flash is manual only (as opposed to TTL), it's a little trickier. I could have used actual math (metering, and then adjusting the settings appropriately based on the reading) but instead I used an educated guess and trial and error, because that's how I roll. My histogram helped me to quickly find acceptable settings. Once I'd established a baseline correct exposure, it was easy enough to vary my settings by keeping track of which direction and what number of stops I changed, and compensating through my other settings. I left my camera on full manual mode; otherwise my exposure would have been wrong due to the presence of the Speedlite, which would be unaccounted for by the camera's metering (additionally, I wanted a consistent exposure, and manual was the best way to achieve that goal).

Next I positioned myself in front of the backdrop. I used my remote control to take a few test shots, checked them on the LCD of my camera, and returned to take more. Because the background had little contrast, the autofocusing would only be successful when the camera locked onto my socks; this meant I didn't have to manually adjust and lock focus, making my life significantly easier (I could autofocus using the remote instead).

Because I was using a cheap flash, it would not fire if I had live view activated; therefore, I had no assistance in positioning myself. Basically, I shot a few frames, checked them on playback, and repeated, occasionally adjusting my aperture to get a different depth of field, and either ISO speed or flash power to keep my exposure the same.

Once I had a lot of shots in a variety of poses, I was done, except for a small amount of post-processing work (mainly tweaking white balance and cropping).

What I Wish I'd Done Differently

And remember to check out Unassuming Socks, available now! It's a perfectly unisex vanilla-plus pattern for the beginner sock knitter, or the advanced sock knitter who just wants some good TV knitting.

| |

| Unassuming Socks by Shannon Donald 50mm (80mm equivalent); 1/60 @ f/4.5, ISO 800 + bounced external flash. |

The Location

The photos were taken in my rather messy basement, on a February evening. Not much natural light happening there!

The Equipment

To get these shots, I used the following gear:

- Canon EOS 80D DSLR camera

- Canon EF50mm f/1.8 II lens

- AmazonBasics 60-inch Lightweight Tripod

- Neewer TT560 Flash Speedlite for Canon

- Neewer 9.8 feet/3 m Off Camera Flash Speedlite Cord

- a generic (i.e., I cannot remember the brand) camera remote control

- an old red tablecloth

- an old dresser (more on that in a minute)

The Setup

This is an impressively professional and well-thought-out studio setup. Not.

I tucked an edge of the tablecloth into the top drawer of an old dresser that was sitting in the basement. Voila! A plain red backdrop is born.

I located the tripod several feet away from the backdrop, on its lowest setting. I placed the flash on the tripod, with the flash head pointed up and towards the white wall to the side of my backdrop (assuming I recall correctly, and that I am reading the light in my photos correctly).

The flash was connected to my camera via the Speedlite cord, which allowed it to be triggered off-camera. I situated the camera itself far enough away from my backdrop that I could shoot wide and crop later; this gave me a little more leeway in terms of where I could position myself and still be in the shot. The most professional part of all? I set the camera on a Wii Fit board with a rolled-up sock under the lens to prop it up just a little bit. Pro tips, y'all. Keep it classy.

|

| 50mm (80mm equivalent); 1/60 @ f/4.5, ISO 800 + bounced external flash. |

The Process

The first step was to get the exposure right. Because my (cheap) flash is manual only (as opposed to TTL), it's a little trickier. I could have used actual math (metering, and then adjusting the settings appropriately based on the reading) but instead I used an educated guess and trial and error, because that's how I roll. My histogram helped me to quickly find acceptable settings. Once I'd established a baseline correct exposure, it was easy enough to vary my settings by keeping track of which direction and what number of stops I changed, and compensating through my other settings. I left my camera on full manual mode; otherwise my exposure would have been wrong due to the presence of the Speedlite, which would be unaccounted for by the camera's metering (additionally, I wanted a consistent exposure, and manual was the best way to achieve that goal).

Next I positioned myself in front of the backdrop. I used my remote control to take a few test shots, checked them on the LCD of my camera, and returned to take more. Because the background had little contrast, the autofocusing would only be successful when the camera locked onto my socks; this meant I didn't have to manually adjust and lock focus, making my life significantly easier (I could autofocus using the remote instead).

Because I was using a cheap flash, it would not fire if I had live view activated; therefore, I had no assistance in positioning myself. Basically, I shot a few frames, checked them on playback, and repeated, occasionally adjusting my aperture to get a different depth of field, and either ISO speed or flash power to keep my exposure the same.

Once I had a lot of shots in a variety of poses, I was done, except for a small amount of post-processing work (mainly tweaking white balance and cropping).

|

| 50mm (80mm equivalent); 1/60 @ f 5.6, ISO 400 + bounced external flash. |

What I Wish I'd Done Differently

- put my flash on my camera and my camera on the tripod (because I bounced the flash anyway, it would have made very little difference in lighting)

- increased my shutter speed to maximum sync speed (1/250) to block out any ambient light

- stopped down my aperture for a deeper depth of field

- increased flash power (even though it would take longer for the flash to cycle)

- chosen a more interesting background

And remember to check out Unassuming Socks, available now! It's a perfectly unisex vanilla-plus pattern for the beginner sock knitter, or the advanced sock knitter who just wants some good TV knitting.

Quick Tip: Instantly Improve Your Cell Phone Photo Quality

Do you use your cell phone camera, either for quick snaps, or as your primary camera? If so, we need to talk about zoom.

One thing most dedicated cameras have that cell phone cameras lack is optical zoom. Optical zoom uses--you guessed it--optics to zoom in or out of your scene. In other words, the lens itself adjusts the zoom.

Digital zoom, on the other hand, is essentially a simulation. Digital zoom enlarges the central portion of the image and cuts away the rest. Basically, it's doing in-camera editing--cropping and enlarging the photograph as you take it, without actually magnifying the scene.

Optical zoom will not result in a loss of quality in your image (or if it does, it will generally not be a significant loss of quality, and any loss in quality will be related to the quality of the lens itself). Digital zoom, on the other hand, will irreparably degrade the quality of your photograph.

So what should you do? Avoid zooming in with your cell phone camera! If possible, get closer to your subject. If you can't get closer, consider cropping in post-processing--at least you'll have more control over the final result.

If you've ever wondered why your cell phone pictures just don't look very good, digital zoom may be the culprit.

One thing most dedicated cameras have that cell phone cameras lack is optical zoom. Optical zoom uses--you guessed it--optics to zoom in or out of your scene. In other words, the lens itself adjusts the zoom.

|

| A photo from my cheap cell phone camera. No zoom used. Click to enlarge. |

Digital zoom, on the other hand, is essentially a simulation. Digital zoom enlarges the central portion of the image and cuts away the rest. Basically, it's doing in-camera editing--cropping and enlarging the photograph as you take it, without actually magnifying the scene.

Optical zoom will not result in a loss of quality in your image (or if it does, it will generally not be a significant loss of quality, and any loss in quality will be related to the quality of the lens itself). Digital zoom, on the other hand, will irreparably degrade the quality of your photograph.

|

| Similar photo, same cheap camera. This time, I used digital zoom. Click to enlarge. Yikes! |

So what should you do? Avoid zooming in with your cell phone camera! If possible, get closer to your subject. If you can't get closer, consider cropping in post-processing--at least you'll have more control over the final result.

If you've ever wondered why your cell phone pictures just don't look very good, digital zoom may be the culprit.

Quick Tip: Learn Some Photo Lingo

Comfortable with terms like "frogging" and "throwing" but lost at "stopping down" and "chimping"? Here is a quick lowdown on some common photographic lingo.

Stopping Down: decreasing the exposure of a shot by increasing shutter speed and/or decreasing aperture value.

Chimping: reviewing images on your camera's LCD screen. Called chimping due to the "ooh ooh" noises that such reviewing tends to produce. Useful in moderation (to check your histogram and composition) but easily overdone.

Dragging the Shutter: using a slow shutter speed with a flash in order to capture some of the ambient light.

Glass: camera lens(es).

Fast Glass: a camera lens with a wide maximum aperture.

Shooting Wide Open: taking pictures at your lens's widest possible aperture.

Bokeh: the aesthetic quality of the area of your image that is out of focus.

Prime: a lens with a fixed focal length (no zoom capability).

Nifty Fifty: a 50mm prime lens. Most DSLR brands offer cheap, fast, nifty fifty options. A great focal length for many purposes.

Pixel Peeper: someone who scrutinizes their photos at 100% on their computer monitor or other screen. Often done to look for small differences in sharpness. Usually a derogatory term.

GAS: Gear Acquisition Syndrome. The longing for evermore photography equipment.

And now you know!

Stopping Down: decreasing the exposure of a shot by increasing shutter speed and/or decreasing aperture value.

Chimping: reviewing images on your camera's LCD screen. Called chimping due to the "ooh ooh" noises that such reviewing tends to produce. Useful in moderation (to check your histogram and composition) but easily overdone.

Dragging the Shutter: using a slow shutter speed with a flash in order to capture some of the ambient light.

Glass: camera lens(es).

Fast Glass: a camera lens with a wide maximum aperture.

Shooting Wide Open: taking pictures at your lens's widest possible aperture.

Bokeh: the aesthetic quality of the area of your image that is out of focus.

Prime: a lens with a fixed focal length (no zoom capability).

Nifty Fifty: a 50mm prime lens. Most DSLR brands offer cheap, fast, nifty fifty options. A great focal length for many purposes.

Pixel Peeper: someone who scrutinizes their photos at 100% on their computer monitor or other screen. Often done to look for small differences in sharpness. Usually a derogatory term.

GAS: Gear Acquisition Syndrome. The longing for evermore photography equipment.

And now you know!

Taking Control: Semi-Manual and Manual Modes

If you have a DSLR, mirrorless, bridge, or advanced point-and-shoot camera, you probably have access to several manual modes for controlling your camera's exposure. These four modes are Program Mode, Shutter Priority Mode, Aperture Priority Mode, and Manual Mode. Used in the right way, these modes can help you to get exactly the photo you want, without the hassle that you don't.

In program, shutter priority, and aperture priority modes, the camera selects the exposure (although it can be modified using exposure compensation). In manual mode, you are in full control of the exposure. Therefore, program, shutter priority, and aperture priority modes are typically considered semi-manual modes since the user influences how the camera exposes, but does not choose the exposure itself.

Program Mode

Program mode is sort of a hybrid mode--an automatic mode that lets you override the camera to one degree or another. The camera does the initial selection of settings, and then you can choose to accept them, or to override them.

The degree of control afforded by program mode varies from camera to camera. On a DSLR, program mode will typically let you adjust ISO, use exposure compensation, and shift between various sets of aperture and shutter values. On a point-and-shoot, program mode may limit you to controlling, for example, exposure compensation only, or it may allow you further control. Consult your camera manual for details.

Shutter Priority Mode

In this mode, you control the shutter speed of your camera, and your camera controls the aperture and ISO speed. You simply set the shutter speed you want, and the camera will adjust the aperture and ISO speed to correctly expose the scene, provided a correct exposure can be achieved with the shutter speed you have chosen.

This last point is important. Your camera cannot do the impossible. If you are in a candlelit room and you set your shutter speed to 1/1000 of a second, your camera simply will not be able to expose the scene correctly; even opening the aperture as wide as possible and cranking the ISO speed to maximum won't achieve a bright enough exposure (unless, maybe, there are so many candles that the room is basically on fire). Conversely, if you're outside in bright sunshine and you set your shutter speed to 10 seconds to try to turn a rushing waterfall into a smooth blur, you'll probably end up with a bright white scene even as your camera closes its aperture and slows down its ISO speed to their minimum possible respective values. Generally speaking, though, shutter priority mode lets you easily achieve a correct exposure at your desired shutter speed without having to fuss about any other settings.

There are a few reasons you might want to choose shutter priority mode, but they all basically boil down to one thing: you care primarily about the speed of your shutter and are willing to sacrifice control over your aperture and/or ISO (you may be able to restrict the range that the camera chooses from, if you so desire). Shutter priority is typically going to be most useful when you want to use a fast shutter speed to capture a quick-moving subject, but you may also use it, for example, to set your camera to the longest shutter speed that you are comfortable hand-holding in low-light conditions.

Aperture Priority Mode

This functions similarly to shutter priority mode, except you control the aperture value instead of the shutter speed, leaving the camera to choose the shutter speed and/or ISO. You might choose aperture priority mode if you want to achieve a specific depth of field, or if you are shooting in low-light conditions and want to use the widest aperture possible.

Manual

Manual mode is exactly as it sounds: you take full manual control over the exposure. Using the in-camera metering system as a guide, you decide which combination of shutter speed, aperture, and ISO your camera will use for the image. If the photo is too dark or too bright, it's your fault!

Manual mode is great if you have a specific vision for your image, if you love to be in control, if you need the exposure to remain the same from one image to the next, or if you're having trouble achieving a correct exposure using one of the other modes. I personally shoot in manual mode the majority of the time, because my camera can't read my mind--only I know exactly what image I want to make.

Some cameras will let you set your ISO to auto in manual mode. Although I typically prefer to control the ISO value myself, I will sometimes switch to auto if I am shooting in rapidly-changing light (especially if I'm shooting a rapidly-moving subject in rapidly-changing light!), or in low light (to keep the ISO value as low as possible when I know what shutter speed and aperture values I want). To add another wrinkle, it can be difficult or impossible to use exposure compensation when using auto ISO. If your camera will let you do so, your manual will tell you how.

So that's about all there is to know about semi-manual and manual modes. Some cameras (such as DSLRs and higher-end compacts) will offer you access to all of these modes; others to some or none. Their particular properties may vary slightly from camera to camera, so it's always a good idea to be familiar with the specifics of your own equipment.

Any questions? Still unclear on anything? Do you have a favourite shooting mode? Drop a comment below!

In program, shutter priority, and aperture priority modes, the camera selects the exposure (although it can be modified using exposure compensation). In manual mode, you are in full control of the exposure. Therefore, program, shutter priority, and aperture priority modes are typically considered semi-manual modes since the user influences how the camera exposes, but does not choose the exposure itself.

Program Mode

Program mode is sort of a hybrid mode--an automatic mode that lets you override the camera to one degree or another. The camera does the initial selection of settings, and then you can choose to accept them, or to override them.

The degree of control afforded by program mode varies from camera to camera. On a DSLR, program mode will typically let you adjust ISO, use exposure compensation, and shift between various sets of aperture and shutter values. On a point-and-shoot, program mode may limit you to controlling, for example, exposure compensation only, or it may allow you further control. Consult your camera manual for details.

Shutter Priority Mode

In this mode, you control the shutter speed of your camera, and your camera controls the aperture and ISO speed. You simply set the shutter speed you want, and the camera will adjust the aperture and ISO speed to correctly expose the scene, provided a correct exposure can be achieved with the shutter speed you have chosen.

This last point is important. Your camera cannot do the impossible. If you are in a candlelit room and you set your shutter speed to 1/1000 of a second, your camera simply will not be able to expose the scene correctly; even opening the aperture as wide as possible and cranking the ISO speed to maximum won't achieve a bright enough exposure (unless, maybe, there are so many candles that the room is basically on fire). Conversely, if you're outside in bright sunshine and you set your shutter speed to 10 seconds to try to turn a rushing waterfall into a smooth blur, you'll probably end up with a bright white scene even as your camera closes its aperture and slows down its ISO speed to their minimum possible respective values. Generally speaking, though, shutter priority mode lets you easily achieve a correct exposure at your desired shutter speed without having to fuss about any other settings.

There are a few reasons you might want to choose shutter priority mode, but they all basically boil down to one thing: you care primarily about the speed of your shutter and are willing to sacrifice control over your aperture and/or ISO (you may be able to restrict the range that the camera chooses from, if you so desire). Shutter priority is typically going to be most useful when you want to use a fast shutter speed to capture a quick-moving subject, but you may also use it, for example, to set your camera to the longest shutter speed that you are comfortable hand-holding in low-light conditions.

Aperture Priority Mode

This functions similarly to shutter priority mode, except you control the aperture value instead of the shutter speed, leaving the camera to choose the shutter speed and/or ISO. You might choose aperture priority mode if you want to achieve a specific depth of field, or if you are shooting in low-light conditions and want to use the widest aperture possible.

Manual

Manual mode is exactly as it sounds: you take full manual control over the exposure. Using the in-camera metering system as a guide, you decide which combination of shutter speed, aperture, and ISO your camera will use for the image. If the photo is too dark or too bright, it's your fault!

Manual mode is great if you have a specific vision for your image, if you love to be in control, if you need the exposure to remain the same from one image to the next, or if you're having trouble achieving a correct exposure using one of the other modes. I personally shoot in manual mode the majority of the time, because my camera can't read my mind--only I know exactly what image I want to make.

Some cameras will let you set your ISO to auto in manual mode. Although I typically prefer to control the ISO value myself, I will sometimes switch to auto if I am shooting in rapidly-changing light (especially if I'm shooting a rapidly-moving subject in rapidly-changing light!), or in low light (to keep the ISO value as low as possible when I know what shutter speed and aperture values I want). To add another wrinkle, it can be difficult or impossible to use exposure compensation when using auto ISO. If your camera will let you do so, your manual will tell you how.

So that's about all there is to know about semi-manual and manual modes. Some cameras (such as DSLRs and higher-end compacts) will offer you access to all of these modes; others to some or none. Their particular properties may vary slightly from camera to camera, so it's always a good idea to be familiar with the specifics of your own equipment.

Any questions? Still unclear on anything? Do you have a favourite shooting mode? Drop a comment below!

Seven Ways to Improve Your Fibre Photos

Want to improve your knit, crochet, or other fibre art photography? Here are some ideas.

1. Read your camera manual.

I will probably harp on this in at least 50% of the posts I write about photography. That's because it's really, really important. If you know how your camera works, you have a much better chance of making it do what you want, when you want. You also won't waste valuable time (and possibly valuable light) trying to figure out if and where you can change a particular setting, or doing excessive trial and error in hopes of somehow getting the shot you want. Don't understand something in your manual? Google it. You never know when you'll need that piece of knowledge.

2. Work with your light.

Photography is all about light. If you don't work with your light, your photo will suffer for it--and this is as true for product photography as it is for art photography. Unless you're well-versed in the use of artificial lighting, your best bet is probably to stick with natural light. Although an overcast day might not give you beautiful blue skies in the background, it will provide you with soft, diffused light. This light is almost universally flattering. It might be a bit flat for an artistic shot, but it'll do very nicely for taking a pattern photo.

On the other hand, direct sunlight can be more difficult to work with (it certainly can be done, but it requires some experience, and often the use of fill flash and/or auxiliary equipment). If you must take photos on a sunny day, try positioning your subject in the shade, just at the edge, so the subject gets some softer light. If your subject is still suffering from hard shadows or a dark face, this is a time when you actually should use your flash. It'll help to fill in the shadows and get you a more even exposure.

Can't get outside? Position your subject next to a large window or another source of natural light. If possible, turn off other light sources such as overhead light. Can't do that either? At the very least, avoid on-camera flash, and play with your white balance to eliminate unflattering colour casts from the artificial light in your scene. Consider using a tripod, since lower light will probably lead to longer shutter speeds and will introduce the risk of camera shake, which results in blurred photos.

3. Consider your background.

Before you snap your photo, look all around your frame--whether it's your viewfinder, or an LCD screen. Watch for things like trash, or the corner of a piece of furniture, or your cat's tail. Unintended objects in a frame can draw attention away from where you want it, towards where you don't. Keeping your backgrounds clean is one of the quickest ways to improve your photos. Don't be afraid to move things to tidy up your background (or your foreground, for that matter)!

Think about how your background can contribute to or detract from your item. Are you trying to photograph a light blue mitten against white snow? Chances are, you'll lose some details. Try to find something with better contrast. Or are you trying to photograph a winter hat on what is clearly a bright summer day? Try to find a background that looks at least a little more appropriate for cold-weather gear. Avoid backgrounds that are visually busy; you want the focus on your subject, not your surroundings. Instead, choose backgrounds that make sense--backgrounds that somehow relate to the item, and show it off to its best advantage.

4. Place your elements intentionally.

Don't just centre your item in the frame and then snap the photo. Consider details, such as where limbs start and end (in a modeled shoot), or whether something might look better off to one side. Are you too far away from your subject, leaving it small in the frame? Move closer, or zoom in. Are you missing just one small portion of your subject, or feel like there's no breathing space around it? Move further away, or zoom out. If you're including props, consider where you want to place them. Don't obscure the best details of your design by placing the prop in between the details and the camera.

Consider also whether a horizontal or a vertical orientation is most appropriate. Often this will be obvious; if the item is wider than it is tall, it will generally work better in horizontal (landscape) orientation; if the item is taller than it is wide, it will generally work better in vertical (portrait) orientation. If you're not sure, take a few shots in both orientations and decide later, when you can see your images on your much larger computer screen. And even if the orientation seems obvious, consider shooting a few snaps in the other direction anyway--you might surprise yourself with what works.

Basically, everything in the frame should be in the frame, and in a specific location in the frame, because you intend for it to be there. Obviously this isn't always possible, but it should be the goal.

5. Use props wisely.

A photo can be greatly improved by the inclusion of some props, but these props should make sense. For example, placing a lace shawl on a table next to some fine jewellery makes sense; placing that same shawl next to a frying pan probably doesn't! You might want to style a pair of hands in mittens, and having those hands hold a snowball or a Christmas ornament would look great, but you probably want to avoid having them hold a popsicle!

Those examples are obvious, but there are more nuanced pitfalls, too. For instance, if you're positioning a knit item with some knitting-related items, you might want to avoid placing scissors in the shot. Maybe it's just a personal thing (and I know we use scissors near finished items all the time, to trim ends and so on), but seeing scissors next to a beautiful knit object always makes me cringe just a little, and worry that something will accidentally be destroyed. Likewise, lit candles near knitting make me just a little nervous. This is more a matter of personal taste, but I think it is something to be at least conscious of when planning your images.

6. Tell a story.

You definitely want to focus on the design itself, but if you can include an element of story, your pictures will be more compelling--encouraging your viewers to focus on them for longer. Maybe you can relate your subject's surroundings to your pattern name. Maybe you can display a shawl on someone pictured preparing for a fancy night out. Maybe your blanket can be shown on someone lounging with a mug and a book. Emotional involvement makes for a more compelling photo!

7. Learn basic post-processing.

You don't have to be a whiz, but the ability to do some basic adjustments to your photo can be immensely helpful in improving image quality. Make sure your horizons are straight, and anything that should be vertical is vertical. Is your white balance correct? Could your image benefit from a bit of sharpening (but don't go overboard, and don't bother trying to fix a blurred or out of focus image--it won't work)? Maybe you need to bump up the saturation a bit? Does your model have a pimple in the middle of her forehead that's attracting attention away from your beautiful hat?

You don't want your image to look obviously processed, but sometimes doing a bit of post-processing work can make your photo look closer to your original vision, or can simply make it more attractive or eye-catching. You may not love investing the time to learn new software, but it will almost always pay off.

What has made the most difference in improving your photos? Where do you still need to do some work? What tips do you have for your fellow fibre artists? Let me know in the comments!

1. Read your camera manual.

I will probably harp on this in at least 50% of the posts I write about photography. That's because it's really, really important. If you know how your camera works, you have a much better chance of making it do what you want, when you want. You also won't waste valuable time (and possibly valuable light) trying to figure out if and where you can change a particular setting, or doing excessive trial and error in hopes of somehow getting the shot you want. Don't understand something in your manual? Google it. You never know when you'll need that piece of knowledge.

2. Work with your light.

Photography is all about light. If you don't work with your light, your photo will suffer for it--and this is as true for product photography as it is for art photography. Unless you're well-versed in the use of artificial lighting, your best bet is probably to stick with natural light. Although an overcast day might not give you beautiful blue skies in the background, it will provide you with soft, diffused light. This light is almost universally flattering. It might be a bit flat for an artistic shot, but it'll do very nicely for taking a pattern photo.

On the other hand, direct sunlight can be more difficult to work with (it certainly can be done, but it requires some experience, and often the use of fill flash and/or auxiliary equipment). If you must take photos on a sunny day, try positioning your subject in the shade, just at the edge, so the subject gets some softer light. If your subject is still suffering from hard shadows or a dark face, this is a time when you actually should use your flash. It'll help to fill in the shadows and get you a more even exposure.

|

| In a matter of seconds, the diffused sunlight from the window I was working with turned into this harsh, direct light, destroying the image. |

Can't get outside? Position your subject next to a large window or another source of natural light. If possible, turn off other light sources such as overhead light. Can't do that either? At the very least, avoid on-camera flash, and play with your white balance to eliminate unflattering colour casts from the artificial light in your scene. Consider using a tripod, since lower light will probably lead to longer shutter speeds and will introduce the risk of camera shake, which results in blurred photos.

|

| Soft light from a window in another room. |

3. Consider your background.

Before you snap your photo, look all around your frame--whether it's your viewfinder, or an LCD screen. Watch for things like trash, or the corner of a piece of furniture, or your cat's tail. Unintended objects in a frame can draw attention away from where you want it, towards where you don't. Keeping your backgrounds clean is one of the quickest ways to improve your photos. Don't be afraid to move things to tidy up your background (or your foreground, for that matter)!

|

| Ugly light, ugly background--is there anything about this picture that is right? |

Think about how your background can contribute to or detract from your item. Are you trying to photograph a light blue mitten against white snow? Chances are, you'll lose some details. Try to find something with better contrast. Or are you trying to photograph a winter hat on what is clearly a bright summer day? Try to find a background that looks at least a little more appropriate for cold-weather gear. Avoid backgrounds that are visually busy; you want the focus on your subject, not your surroundings. Instead, choose backgrounds that make sense--backgrounds that somehow relate to the item, and show it off to its best advantage.

|

| Soft light and a clean background. A bit boring, maybe, but a much better representation of the socks. |

4. Place your elements intentionally.

Don't just centre your item in the frame and then snap the photo. Consider details, such as where limbs start and end (in a modeled shoot), or whether something might look better off to one side. Are you too far away from your subject, leaving it small in the frame? Move closer, or zoom in. Are you missing just one small portion of your subject, or feel like there's no breathing space around it? Move further away, or zoom out. If you're including props, consider where you want to place them. Don't obscure the best details of your design by placing the prop in between the details and the camera.

Consider also whether a horizontal or a vertical orientation is most appropriate. Often this will be obvious; if the item is wider than it is tall, it will generally work better in horizontal (landscape) orientation; if the item is taller than it is wide, it will generally work better in vertical (portrait) orientation. If you're not sure, take a few shots in both orientations and decide later, when you can see your images on your much larger computer screen. And even if the orientation seems obvious, consider shooting a few snaps in the other direction anyway--you might surprise yourself with what works.

Basically, everything in the frame should be in the frame, and in a specific location in the frame, because you intend for it to be there. Obviously this isn't always possible, but it should be the goal.

5. Use props wisely.

A photo can be greatly improved by the inclusion of some props, but these props should make sense. For example, placing a lace shawl on a table next to some fine jewellery makes sense; placing that same shawl next to a frying pan probably doesn't! You might want to style a pair of hands in mittens, and having those hands hold a snowball or a Christmas ornament would look great, but you probably want to avoid having them hold a popsicle!

|

| Okay, it's a cute enough teddy, I guess, but why is it there? |

Those examples are obvious, but there are more nuanced pitfalls, too. For instance, if you're positioning a knit item with some knitting-related items, you might want to avoid placing scissors in the shot. Maybe it's just a personal thing (and I know we use scissors near finished items all the time, to trim ends and so on), but seeing scissors next to a beautiful knit object always makes me cringe just a little, and worry that something will accidentally be destroyed. Likewise, lit candles near knitting make me just a little nervous. This is more a matter of personal taste, but I think it is something to be at least conscious of when planning your images.

6. Tell a story.

You definitely want to focus on the design itself, but if you can include an element of story, your pictures will be more compelling--encouraging your viewers to focus on them for longer. Maybe you can relate your subject's surroundings to your pattern name. Maybe you can display a shawl on someone pictured preparing for a fancy night out. Maybe your blanket can be shown on someone lounging with a mug and a book. Emotional involvement makes for a more compelling photo!

|

| Shampoo bottles and a towel make sense with a washcloth, and bring to mind a day at the spa. |

7. Learn basic post-processing.

You don't have to be a whiz, but the ability to do some basic adjustments to your photo can be immensely helpful in improving image quality. Make sure your horizons are straight, and anything that should be vertical is vertical. Is your white balance correct? Could your image benefit from a bit of sharpening (but don't go overboard, and don't bother trying to fix a blurred or out of focus image--it won't work)? Maybe you need to bump up the saturation a bit? Does your model have a pimple in the middle of her forehead that's attracting attention away from your beautiful hat?

|

| Processing matters! |

You don't want your image to look obviously processed, but sometimes doing a bit of post-processing work can make your photo look closer to your original vision, or can simply make it more attractive or eye-catching. You may not love investing the time to learn new software, but it will almost always pay off.

What has made the most difference in improving your photos? Where do you still need to do some work? What tips do you have for your fellow fibre artists? Let me know in the comments!

What the Heck is Raw, and Should I Use It?

If you spend much time exposed to photography talk, you'll soon start to hear the term "raw" bandied about (and you'll probably hear some strong opinions about how shooting raw is the best thing since sliced bread--or perhaps since plied yarn--or, alternatively, how it's a big waste of time and hard drive space). But what is raw?

A raw file, unlike a JPEG, is not an image. Rather, a raw file contains the information necessary to create an image. The information it contains was obtained at the time the particular photograph was made. Raw is often referred to as a digital negative since it is not usable without processing. The great advantage of a raw file is that it contains all of the information collected by the sensor when the photograph was taken. A JPEG, on the other hand, has compressed and discarded a significant portion of this data. This makes the raw file much more flexible than its processed counterpart. Raw files are also edited non-destructively, which means that you can do pretty much whatever you want to them without causing a decrease in the file quality (and you can't accidentally do something awful to your image and then save over the original, forever ruining it!). Basically, when you edit a raw file, you're just telling it how to display (and eventually create) the image it holds information about, without actually altering the file data. JPEGs, on the other hand, tend to degrade whenever you edit them, and because they have less information to begin with, you are more limited in the edits you can make.

More data, more flexibility, and non-destructive editing--sounds great, right? Unfortunately, there are a few disadvantages to shooting raw. First, raw files are significantly larger than JPEG files, so they will take up more space on your memory card (in camera) and your computer (after transfer) than the corresponding JPEG. Second, raw files require processing with specialised software. Processing will require additional time in your workflow (although once you are familiar with your raw processor, it can be quite fast), and many raw processors have a significant learning curve. If you don't get to know your raw processor well, your images may not look as good after processing as they would have if you'd just let your camera do all the work in the first place. Third, if you want to shoot many images in quick succession, shooting raw will limit you, because the larger files take up more space in the camera buffer.

So should you, as a fibre artist, shoot in raw? Ultimately, it's your decision, but here are some questions to consider:

Earlier in my foray into raw processing, I used Canon's proprietary raw development software, Digital Photo Professional [DPP]. One of its benefits is that (as far as I can tell), your starting point for editing your raw file is the same as the JPEG you would have gotten out of your camera. Personally, I now find DPP rather limiting, but it was a nice way for me to ease into developing raw files. If you don't shoot a Canon camera you won't be able to use DPP, but you may want to look into whether your camera brand has its own raw processing software (most do), and see if you like it.

If you're interested in shooting raw, you can check out my post about raw processing software here. I hope you found this a helpful introduction to raw files. Happy shooting!

A raw file, unlike a JPEG, is not an image. Rather, a raw file contains the information necessary to create an image. The information it contains was obtained at the time the particular photograph was made. Raw is often referred to as a digital negative since it is not usable without processing. The great advantage of a raw file is that it contains all of the information collected by the sensor when the photograph was taken. A JPEG, on the other hand, has compressed and discarded a significant portion of this data. This makes the raw file much more flexible than its processed counterpart. Raw files are also edited non-destructively, which means that you can do pretty much whatever you want to them without causing a decrease in the file quality (and you can't accidentally do something awful to your image and then save over the original, forever ruining it!). Basically, when you edit a raw file, you're just telling it how to display (and eventually create) the image it holds information about, without actually altering the file data. JPEGs, on the other hand, tend to degrade whenever you edit them, and because they have less information to begin with, you are more limited in the edits you can make.

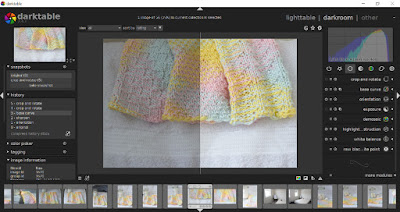

|

| Developing a raw file using darktable for Windows |

More data, more flexibility, and non-destructive editing--sounds great, right? Unfortunately, there are a few disadvantages to shooting raw. First, raw files are significantly larger than JPEG files, so they will take up more space on your memory card (in camera) and your computer (after transfer) than the corresponding JPEG. Second, raw files require processing with specialised software. Processing will require additional time in your workflow (although once you are familiar with your raw processor, it can be quite fast), and many raw processors have a significant learning curve. If you don't get to know your raw processor well, your images may not look as good after processing as they would have if you'd just let your camera do all the work in the first place. Third, if you want to shoot many images in quick succession, shooting raw will limit you, because the larger files take up more space in the camera buffer.

So should you, as a fibre artist, shoot in raw? Ultimately, it's your decision, but here are some questions to consider:

- Does your camera even let you shoot raw? Many--and perhaps even most--do, but check your manual if you're not sure. If not, you're stuck with JPEG.

- Are you willing to learn to use a new piece of software? If not, stick with JPEG.

- Do you have very limited storage space for your image files? If so, you probably want to stick with JPEG.

- Are you interested in photography beyond your fibre art needs? If so, consider raw.

- Do you typically edit your JPEG files? If so, consider raw.

- Do you often forget to set your white balance in camera? If so, consider raw--you can change it when you develop your raw file without degrading your image.

- Do you frequently mess up your exposure, or shoot in uneven lighting conditions or with a broad dynamic range? If so, consider raw--you'll be able to recover a lot of extra image data.

- Do you want the highest possible image quality? If so, shoot raw.

- Are you just curious what all the fuss is about? Try raw!

Earlier in my foray into raw processing, I used Canon's proprietary raw development software, Digital Photo Professional [DPP]. One of its benefits is that (as far as I can tell), your starting point for editing your raw file is the same as the JPEG you would have gotten out of your camera. Personally, I now find DPP rather limiting, but it was a nice way for me to ease into developing raw files. If you don't shoot a Canon camera you won't be able to use DPP, but you may want to look into whether your camera brand has its own raw processing software (most do), and see if you like it.

If you're interested in shooting raw, you can check out my post about raw processing software here. I hope you found this a helpful introduction to raw files. Happy shooting!

Ten Signs Your Photography is Improving

I removed a pole from my husband's head while I was shooting him the other day.

Okay, so what I actually did was change my position while taking pictures of him when I realised that there was a telephone pole centred behind his head in the photo, and that not moving would make the final photo look as though he was growing said pole from his head. But it happened on a day when I was feeling particularly discouraged. My photographs were boring, and I was still fumbling with my buttons, and I'd just tried to handhold a shot with too slow a shutter speed for my focal length, because I'd been lazy about changing my settings to match the lens I'd just put on my camera.

Removing that telephone pole gave me hope, because seeing it in the first place means that I'm seeing better now than I was a few weeks ago. A few weeks ago, all of my photos would have had that pole growing out of his head, rather than only the first few.

Progress in photography is sometimes, but not always, visible in your photographs. So what are some ways to know that you're growing in your craft? Here are ten (but there are many more).

1. Your photos look better.

This one doesn't need much explanation. Your photos look better because you're better, and you rely less on luck.

2. Your photos look worse.

This isn't always a sign of growth, but it certainly can be. Maybe your photos look worse because you're starting to take more control over your camera settings. Maybe you're experimenting with angles instead of sticking to what's safe. Maybe you're using a new lens with a new focal length, and you're not used to its effects on your photos. Maybe you're shooting Raw and working on your Raw developing/post-processing skills. Whatever the reason, your photos might look a whole lot worse shortly before they start to look a whole lot better.

3. Your photos look like you expect them to look.

If you can envision your shot before you take it, and the shot you take looks like your vision, you are well on your way to mastering photography (but maybe it's time to experiment with a new focal length or a new technique some of the time).

4. You notice objects in the background and edges of your frame before you shoot.

We're really good at seeing only our subject, and ignoring detritus and distractions. Learning to see like a photographer includes looking at every corner of the frame and deciding which elements you want to include and exclude. Fewer shots with distractions in the corners or with trees growing out of people's heads demonstrates progress!

5. You crop less.

This is related to the previous two points. If you know what your photo will look like, and you have excluded unwanted elements from the frame, you'll find yourself having to crop your image much less frequently. You'll get the framing right in camera instead.

6. You are able to offer more detailed critiques of photos.

Part of seeing is being able to see elements within the final shot--whether it's your photo or another person's. When you start to be able to see why a photo works or doesn't, including little things like a distracting blob of colour in the background or a nuanced use of supplementary light, you'll also be better at seeing these things through your lens and adjusting--or not--accordingly.

7. You think more before you shoot.

You don't just "spray and pray". You think about what you want to capture, what angle might best allow you to do so, and perhaps even whether it's worth pressing the shutter button. Basically, you weed out a lot of your shots before you even take them (but don't go overboard on this! Taking "sketch images", as David duChemin calls them, is usually an important part of the process).

8. You adjust your settings with intentionality.

You choose to shoot with a certain aperture, shutter speed, and ISO, rather than just letting them happen. You consider what metering mode might be the most helpful. You decide which autofocus mode best suits your needs, or you switch to manual focus if your camera is struggling. Your camera is there to serve your vision, rather than to confuse you.

9. You think about the light in your shot.

You consider where the light is coming from and how that will affect your subject. You judge whether the light is hard or soft, and you plan your shot accordingly. You consider whether the light suits your purpose, or if you need to change it in some way.

10. You modify the light in your shot.

You're in a situation with light that doesn't meet your needs--so you change it. You move your subject to shade. You add light with a reflector or a flash. You flag the light. Basically, you make the light do what you want it to do, instead of simply doing what it's already doing.

How have you known that your photography was improving? What improvement are you seeing right now?

Okay, so what I actually did was change my position while taking pictures of him when I realised that there was a telephone pole centred behind his head in the photo, and that not moving would make the final photo look as though he was growing said pole from his head. But it happened on a day when I was feeling particularly discouraged. My photographs were boring, and I was still fumbling with my buttons, and I'd just tried to handhold a shot with too slow a shutter speed for my focal length, because I'd been lazy about changing my settings to match the lens I'd just put on my camera.

Removing that telephone pole gave me hope, because seeing it in the first place means that I'm seeing better now than I was a few weeks ago. A few weeks ago, all of my photos would have had that pole growing out of his head, rather than only the first few.

Progress in photography is sometimes, but not always, visible in your photographs. So what are some ways to know that you're growing in your craft? Here are ten (but there are many more).

1. Your photos look better.

This one doesn't need much explanation. Your photos look better because you're better, and you rely less on luck.

|

| 154mm; 1/250 @ f/5.6, ISO 1600 It's not perfect, but a few months ago, I would not have seen this shot. |

2. Your photos look worse.

This isn't always a sign of growth, but it certainly can be. Maybe your photos look worse because you're starting to take more control over your camera settings. Maybe you're experimenting with angles instead of sticking to what's safe. Maybe you're using a new lens with a new focal length, and you're not used to its effects on your photos. Maybe you're shooting Raw and working on your Raw developing/post-processing skills. Whatever the reason, your photos might look a whole lot worse shortly before they start to look a whole lot better.

3. Your photos look like you expect them to look.

If you can envision your shot before you take it, and the shot you take looks like your vision, you are well on your way to mastering photography (but maybe it's time to experiment with a new focal length or a new technique some of the time).

4. You notice objects in the background and edges of your frame before you shoot.

We're really good at seeing only our subject, and ignoring detritus and distractions. Learning to see like a photographer includes looking at every corner of the frame and deciding which elements you want to include and exclude. Fewer shots with distractions in the corners or with trees growing out of people's heads demonstrates progress!

5. You crop less.

This is related to the previous two points. If you know what your photo will look like, and you have excluded unwanted elements from the frame, you'll find yourself having to crop your image much less frequently. You'll get the framing right in camera instead.

|

| 250mm; 1/320 @ f/5.6, ISO 2000 Framed exactly how I wanted it in camera. |

6. You are able to offer more detailed critiques of photos.

Part of seeing is being able to see elements within the final shot--whether it's your photo or another person's. When you start to be able to see why a photo works or doesn't, including little things like a distracting blob of colour in the background or a nuanced use of supplementary light, you'll also be better at seeing these things through your lens and adjusting--or not--accordingly.

|

| 194mm; 1/500 @ f/5.6, ISO 2000 I am now able to see how much stronger this shot would have been if I'd shifted an inch or two to the right. |

7. You think more before you shoot.

You don't just "spray and pray". You think about what you want to capture, what angle might best allow you to do so, and perhaps even whether it's worth pressing the shutter button. Basically, you weed out a lot of your shots before you even take them (but don't go overboard on this! Taking "sketch images", as David duChemin calls them, is usually an important part of the process).

|

| 171mm; 1/500 @ f/5.6, ISO 2000 Intentionally isolated against a simple background after carefully considering multiple angles. |

8. You adjust your settings with intentionality.

You choose to shoot with a certain aperture, shutter speed, and ISO, rather than just letting them happen. You consider what metering mode might be the most helpful. You decide which autofocus mode best suits your needs, or you switch to manual focus if your camera is struggling. Your camera is there to serve your vision, rather than to confuse you.

9. You think about the light in your shot.

You consider where the light is coming from and how that will affect your subject. You judge whether the light is hard or soft, and you plan your shot accordingly. You consider whether the light suits your purpose, or if you need to change it in some way.

10. You modify the light in your shot.

You're in a situation with light that doesn't meet your needs--so you change it. You move your subject to shade. You add light with a reflector or a flash. You flag the light. Basically, you make the light do what you want it to do, instead of simply doing what it's already doing.

How have you known that your photography was improving? What improvement are you seeing right now?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)